In the fall and winter of 1873 Englishwoman Isabella Bird traveled alone through the Rocky Mountains, usually by horseback and often over rough terrain and in miserable weather, encountering along the way desperadoes, Indians, and other characters of the Wild West.

Deer Valley [Colorado], November. Tonight I am in a beautiful place like a Dutch farm—large, warm, bright, clean, with abundance of clean food, and a clean, cold little bedroom to myself. But it is very hard to write, for two free-tongued, noisy Irish women, who keep a miners’ boarding house in South Park, and are going to winter quarters in a freight wagon, are telling the most fearful stories of violence, vigilance committees, Lynch law, and “stringing” that I ever heard.

It turns one’s blood cold only to think that where I travel in perfect security, only a short time ago men were being shot like skunks. At the mining towns up above this nobody is thought anything of who has not killed a man—i.e., in a certain set. These women had a boarder, only fifteen, who thought he could not be anything till he had shot somebody, and they gave an absurd account of the lad dodging about with a revolver, and not getting up courage enough to insult anyone, till at last he hid himself in the stable and shot the first Chinaman who entered.

Things up there are just in that initial state which desperadoes love. A man accidentally shoves another in a saloon, or says a rough word at meals, and the challenge, “first finger on the trigger,” warrants either in shooting the other at any subsequent time without the formality of a duel. Nearly all the shooting affrays arise from the most trivial causes in saloons and barrooms. The deeper quarrels, arising from jealousy or revenge, are few, and are usually about some woman not worth fighting for.

At Alma and Fairplay, vigilance committees have been lately formed, and when men act outrageously and make themselves generally obnoxious they receive a letter with a drawing of a tree, a man hanging from it, and a coffin below, on which is written “Forewarned.” They “git” in a few hours.

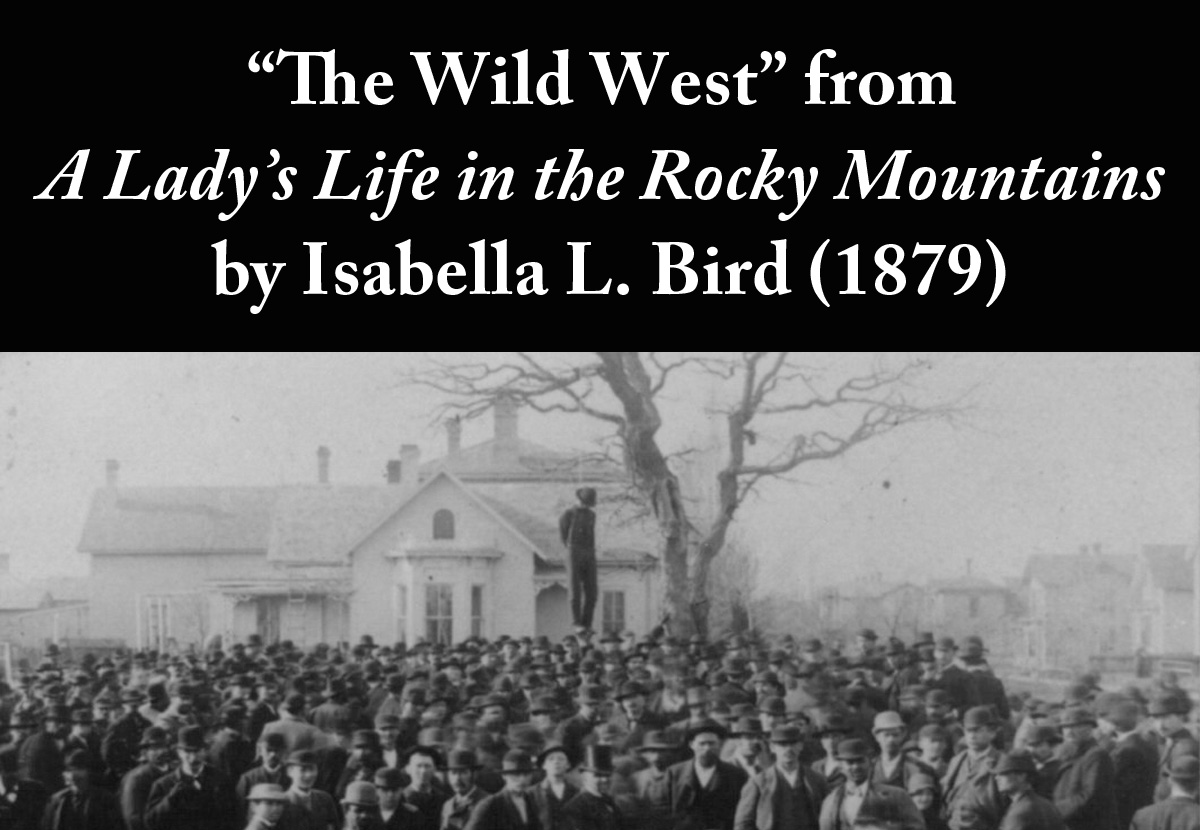

When I said I spent last night at Hall’s Gulch there was quite a chorus of exclamations. My host there, they all said, would be “strung” before long. Did I know that a man was “strung” there yesterday? Had I not seen him hanging? He was on the big tree by the house, they said. Certainly, had I known what a ghastly burden that tree bore, I would have encountered the ice and gloom of the gulch rather than have slept there. They then told me a horrid tale of crime and violence. This man had even shocked the morals of the Alma crowd, and had a notice served on him by the vigilants, which had the desired effect, and he migrated to Hall’s Gulch. As the tale runs, the Hall’s Gulch miners were resolved either not to have a groggery or to limit the number of such places, and when this ruffian set one up he was “forewarned.” It seems, however, to have been merely a pretext for getting rid of him, for it was hardly a crime of which even Lynch law could take cognizance. He was overpowered by numbers, and, with circumstances of great horror, was tried and strung on that tree within an hour....

I could not make out whether the superiority of the Deer Valley settlers extended beyond material things, but a teamster I met in the evening said it “made him more of a man to spend a night in such a house.” In Colorado whisky is significant of all evil and violence and is the cause of most of the shooting affrays in the mining camps. There are few moderate drinkers; it is seldom taken except to excess. The great local question in the Territory, and just now the great electoral issue, is drink or no drink, and some of the papers are openly advocating a prohibitive liquor law.

Some of the districts, such as Greeley, in which liquor is prohibited, are without crime, and in several of the stock-raising and agricultural regions through which I have traveled where it is practically excluded, the doors are never locked, and the miners leave their silver bricks in their wagons unprotected at night. People say that on coming from the eastern states they hardly realize at first the security in which they live. There is no danger and no fear.

But the truth of the proverbial saying “There is no God west of the Missouri” is everywhere manifest. The “almighty dollar” is the true divinity, and its worship is universal. “Smartness” is the quality thought most of. The boy who “gets on” by cheating at his lessons is praised for being a “smart boy,” and his satisfied parents foretell that he will make a “smart man.” A man who overreaches his neighbor, but who does it so cleverly that the law cannot take hold of him, wins an envied reputation as a “smart man,” and stories of this species of smartness are told admiringly round every stove. Smartness is but the initial stage of swindling, and the clever swindler who evades or defines the weak and often corruptly administered laws of the States excites unmeasured admiration among the masses.

I left Deer Valley at ten the next morning on a glorious day, with rich atmospheric coloring, had to spend three hours sitting on a barrel in a forge after I had ridden twelve miles, waiting while twenty-four oxen were shod, and then rode on twenty-three miles through streams and canyons of great beauty till I reached a grocery store, where I had to share a room with a large family and three teamsters; and being almost suffocated by the curtain partition, got up at four, before anyone was stirring, saddled Birdie, and rode away in the darkness, leaving my money on the table!

It was a short eighteen miles’ ride to Denver down the Turkey Creek Canyon, which contains some magnificent scenery, and then the road ascends and hangs on the ledge of a precipice 600 feet in depth, such a narrow road that on meeting a wagon I had to dismount for fear of hurting my feet with the wheels. From thence there was a wonderful view through the rolling foothills and over the gray-brown plains to Denver. Not a tree or shrub was to be seen, everything was rioting in summer heat and drought, while behind lay the last grand canyon of the mountains, dark with pines and cool with snow.

I left the track and took a shortcut over the prairie to Denver, passing through an encampment of the Ute Indians about 500 strong, a disorderly and dirty huddle of lodges, ponies, men, squaws, children, skins, bones, and raw meat. The Americans will never solve the Indian problem till the Indian is extinct. They have treated them after a fashion which has intensified their treachery and “devilry” as enemies, and as friends reduces them to a degraded pauperism, devoid of the very first elements of civilization. The only difference between the savage and the civilized Indian is that the latter carries firearms and gets drunk on whisky.

The Indian Agency has been a sink of fraud and corruption; it is said that barely thirty percent of the allowance ever reaches those for whom it is voted; and the complaints of shoddy blankets, damaged flour, and worthless firearms are universal. “To get rid of the Injuns” is the phrase used everywhere. Even their “reservations” do not escape seizure practically; for if gold “breaks out” on them they are “rushed,” and their possessors are either compelled to accept land farther west or are shot off and driven off. One of the surest agents in their destruction is vitriolized whisky.

An attempt has recently been made to cleanse the Augean stable of the Indian Department, but it has met with signal failure, the usual result in America of every effort to purify the official atmosphere. Americans specially love superlatives. The phrases “biggest in the world,” “finest in the world” are on all lips. Unless President Hayes is a strong man they will soon come to boast that their government is composed of the “biggest scoundrels” in the world.

From A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains by Isabella L. Bird*

Follow Classic Travel Tales on Facebook.

Subscribe to Classic Travel Tales.

New material and editing © 2023 L.A. Mulnix, Publisher.

*L.A. Mulnix, Publisher, participates in the Amazon Associates program, which pays us a small commission on qualified purchases.

Image: Lynching of MacManus by photographer H.R. Farr, 1882, Library of Congress.